“Welcome home,” the stranger said to my husband.

We were in Franklin, Tennessee, about five and a half hours from our house in southern Illinois and ten hours from Pontiac, Michigan, my husband’s birthplace and childhood home. This was our first ever visit to Franklin.

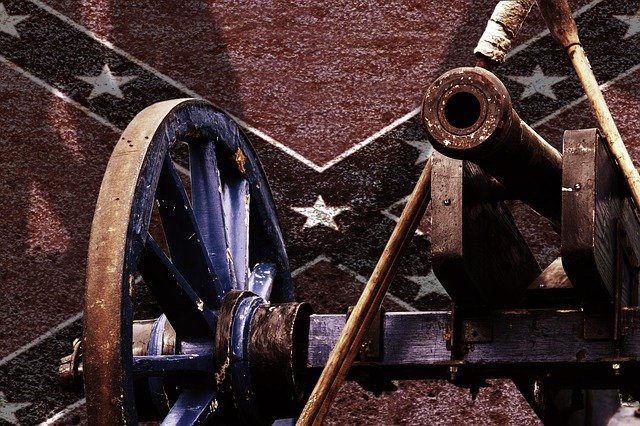

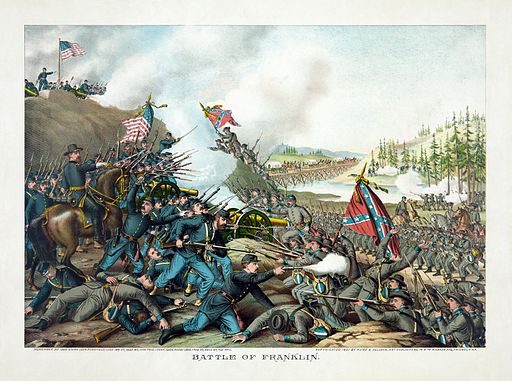

We had just finished a guided tour of the site where the Battle for Franklin took place. There, on November 30, 1864, what some call the five bloodiest hours of the Civil War unfolded. Eight thousand men died.

A few minutes before, the stranger stood with us in the cellar of Fountain Branch Carter’s home, where two dozen Carter relations once pressed fearfully together in the dark and listened to the roar of fighting outside. The tour guide said the din was so loud, they couldn’t hear their own screams.

When they emerged they discovered the carnage — bodies layered upon bodies so deep that soldiers killed late in the fight remained vertical; they had no place to fall.

During this story, I noticed dates and words stitched on the stranger’s blue cap: “1968-1969 Chu Lai, Vietnam.” Something stirred in my memory. I had heard of Chu Lai before.

Among Fountain Branch Carter’s children were three sons who served in the Confederate army. But the soldiers who most recently occupied his home and property wore Federal blue. Union soldiers made Carter’s parlor their headquarters and dug earthwork fortifications in his yard. They dismantled his slave cabins and constructed defense works. Carter’s property was situated on high ground they would not relinquish. They dug in and prepared to welcome the Confederates with fire.

Determined to engage the entrenched Federal troops, Confederate General John Bell Hood ordered his soldiers to advance through two miles of open field, fully exposed to Union fire. His officers argued for other options, but Hood’s will prevailed. Charge followed failed charge, but Hood kept trying. The next charge might just be the one to break through.

Captain Tod Carter, Fountain’s third son, led one of those charges. He took eight bullets to his body and one over his left eye. The next day, his father discovered Tod where he fell, very near the Carter home, still alive. He carried his son — bone of his bone, flesh of his flesh — through the carnage on his homestead to the parlor turned Union command post, home, where basins of water and bandages awaited. Helping hands from family administered aid, but Tod died.

When the tour ended, my husband quietly approached the man with the blue cap. “You served in Chu Lai in ’69?”

“Yes.”

“I was in Duc Pho.”

Soldiers stationed in Chu Lai in 1968 and 1969 knew nearby Duc Pho as the source of artillery support and an airstrip. My husband’s command was in Chu Lai, but his work in radio communications took him to Duc Pho. The two knew each other’s neighborhood in that other time and far away place a lifetime ago when they were young men, quick and strong, clear-eyed and able.

“Welcome home,” said the vet, less a stranger now. Perhaps they shook hands. I don’t remember.

Though tardy, the “welcome home” from one Vietnam vet to another is intended to compensate for the failure of the rest of us to say those words. It acknowledges invisible wounds — invisible then, invisible now.

Welcome home, man in the blue hat; welcome home husband of mine, more than forty years after the fact.

Welcome home, son of my own, bone of my bone and flesh of my flesh, whose status as active duty earned us a discount for the tour. I want to be able to say especially to you, “welcome home” nine months from September when you return home again. Love you and Godspeed.

Photos from top to bottom: (1) Confederate canon: Image by DB-Foto from Pixabay; (2) the Fountain Branch Carter home: Photo: Hal Jespersen, public domain, via Wikimedia Common; (3) The Battle for Franklin: Image source: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons; (4) Chu Lai Air Base: NARA photo 111-CCV-619-CC46213 by SP4 Paul Dupont, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons; (5) Soldiers of the 25th Infantry: National Archives at College Park, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons