Now, it was his: the little pink Barbie two-wheeler that his big sister got as a hand-me down from some older kid he never knew. In his short memory it had always been around.

A faded pink “B” covered the seat. The remnants of plastic streamers stuck out from holes in the ends of its handle grips. A scrap of ribbon left over from last year’s birthday balloon stayed stubbornly knotted around a handlebar. It’s pink training wheels were in the toy box in the garage; he used them for inventions.

His sister, six years old today, now owned a brand new purple bike, a birthday bike with a banana seat and snazzy designs on its fenders and seat. He picked at the little rubbery nubs that stuck out from its unspoiled tires.

The birthday bike smelled good, like the GI Joe aisle in the Value City store. He studied his reflection in the chrome handlebars. He ran his hand down the smooth vinyl seat. The cushiony handle grips sprang back when he squeezed them. Boy, this was good.

The smaller bike, the Barbie bike, was now his to ride—the pink bike with the fenders that rattled over bumps and the dots of rust on the handlebars and the wiggly seat and the chain that slipped sometimes and the clumps of dirt on the pedals.

From his usual place on the seat of his ground-hugging Big Wheels, he had watched his sister lap the block a gazillion times on that Barbie bike. On that seat and behind those handlebars, she made pretend come alive–fast getaways and narrow escapes, times when speed was her only hope. He watched her swing that bike around and follow the bigger kids on their bigger bikes as they zoomed through mud puddles after a rain and whip around corners and race down the back alley.

He had seen her fly that bike through the back gate and into the backyard, right through the open garage door into one of those long smooooooth gliding stops that ended right at dad’s workbench.

These were his wheels now; they just seemed like hers.

Transformed

One weekend after she took the birthday bike on a lap around the block, the hand-me-down Barbie bike appeared as a spread of disconnected parts on the garage floor—a wheel, a pedal, a seat, another pedal, handlebars, a wheel, the chain, and so on and so on. Dad had dismantled it.

“Just wait and see,” he said.

Its frame dangled by wires from a low-hanging tree limb in the back lot where dad applied coat after coat of spray enamel, a bright, super-charged yellow. He returned to the garage and rubbed the handlebars with steel wool. The rusty blemishes disappeared. Chunky black pedals and thick-cushioned black handlebar grips turned up after mom’s trip to the Value City store.

Dad whistled as he put it all together—the refurbished old parts and brand new parts—tightening this, straightening that.

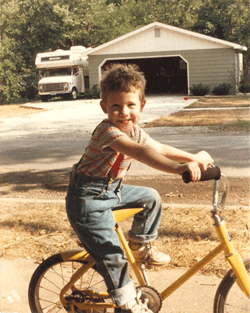

Vinyl with wide black and yellow stripes, cut to size and stretched tightly over the Barbie “B,” gave the seat vibrant new life. It was bold and smooth and perfect.

The old bike was no more. Every inch had succumbed to renewal. This lively version of wheels smelling of unspoiled vinyl and rubber from it’s store-bought additions seemed to laugh out loud all by itself when he mounted it. The tightened frame, grease job and freshly pumped tires beckoned, “Try me!” He did. He lapped the block. It was good. He lapped it again and again . . . really good.

But not quite as good as the wheels that came later—the ones that appeared by the tree on a Christmas morning—new wheels, brand new BMX wheels from grandma and grandpa with a deep red frame and the number 95 streaking across it and firm tires and handlebars connected by a thickly padded cross piece.

His, all his.

Later that sunny snowless morning, mother and son left the others to their Christmas cheer and took their bikes out the back gate, down the alley and around the block twice to get a feel for the ride.

It was good.

And then, instead of lapping the block again, they turned the other way, away from their block and out of the neighborhood. They rode north past the place where the houses ended and the apartments began, north past the trailer park and past the hill someone said was an Indian burial ground, and past the field where they flew kites sometimes and watched the stars one night from blankets on the ground.

They rode by places he had known only through a car window, farther than he had ever biked before. They turned west toward the little country cemetery with its few fenced in headstones, west past the pale fields of dried grasses and stalks. Finally, they turned south back toward town, down the wildly steep hill that plunged into Bluff Street at the bottom. Descent, rush, risk, flying, speed, flying, flying.

In years to come, he would travel on his own to distant places, exotic places, revered and holy places. But on this Christmas morning, this day filled with grace, with the warmth of sun on his back and the gush of air against his face, and folks off the roads, and no rules like “only around the block” and “time for dinner” to reign him in, he gloried in the joy of wheels—new wheels. His wheels.