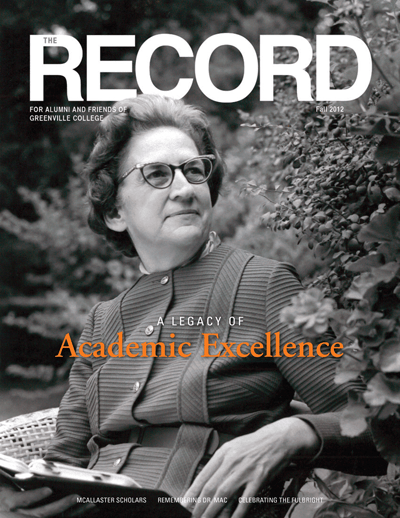

“Come in, come in!” Bone china teacups, cozy living room, polished woodwork, classical music – Elva McAllaster found dozens of ways to graciously welcome students. Ever observant, she tailored her response to the need – a handwritten note, the gift of a book or poem, a magazine article earmarked “just for you,” a promised prayer. Along with the warmth, however, came her expectation for rigorous scholarship. As one student put it, “She cared enough to confront.”

Poet, scholar, and author Eugene Peterson recalls arriving as a freshman at Seattle Pacific College (SPC) in 1950 knowing nothing about the arts. “We didn’t have many books,” he said of his small town upbringing in Montana. “The town itself was totally devoid of anything that had to do with art.” Peterson wrote for the student newspaper at SPC, however, and majored in English – pursuits that put him in the path of a young professor named Elva McAllaster.

Professor of English and advisor to the newspaper staff, McAllaster embraced English literature with zest. She saw literature as life transposed to an art form and delighted in helping others see it that way, too. She arrived at SPC just two years before Peterson, a newly earned Ph.D. from the University of Illinois in hand.

More than 50 years later, Peterson vividly recalls McAllaster’s pause as she read a sentence he composed for his newspaper column. The sentence said, “This was duller than calculus and Chaucer.”

“Eugene,” she said, “Have you ever read Chaucer?”

“No,” he replied, “But I just kind of liked the sound – ‘calculus and Chaucer.’”

McAllaster sent Peterson selections of Chaucer. He dug in, only to discover that “dull” did not apply.

The experience yielded two pleasures for Peterson: (1) Chaucer’s engaging and artful use of language, and (2) McAllaster’s enduring interest in his pursuits. “She kept in touch with me for another 20 years,” he said. “Every time I would write something, she would comment on it.” Peterson went on to author more than 30 books, including his translation, The Message: The Bible in Contemporary Language. McAllaster’s faithful correspondence upon each publication kept their shared dialogue alive.

Tough-minded, gentle, quick to challenge shoddy thought

In 1956, at the call of then Greenville College President H.J. Long, McAllaster left Seattle to teach at GC, her undergraduate alma mater. A member of the Class of 1944, McAllaster valued the prospect of rejoining her mentor and friend, Dr. Mary Tenney. She admired Tenney as “tough-minded, but gentle; quick to challenge shoddy thought in a classroom or conversation; quick to notice the needs and moods of other human beings.” McAllaster valued Tenney’s approach and learned from it. Years later, former GC President Robert Smith used Tenney-like descriptions to recall Dr. Mac’s unwavering dedication to good scholarship. “Elva McAllaster brought her own commitment to academic excellence that made academic administrators like presidents and deans unnecessary. There was no place for mediocrity in her classroom.”

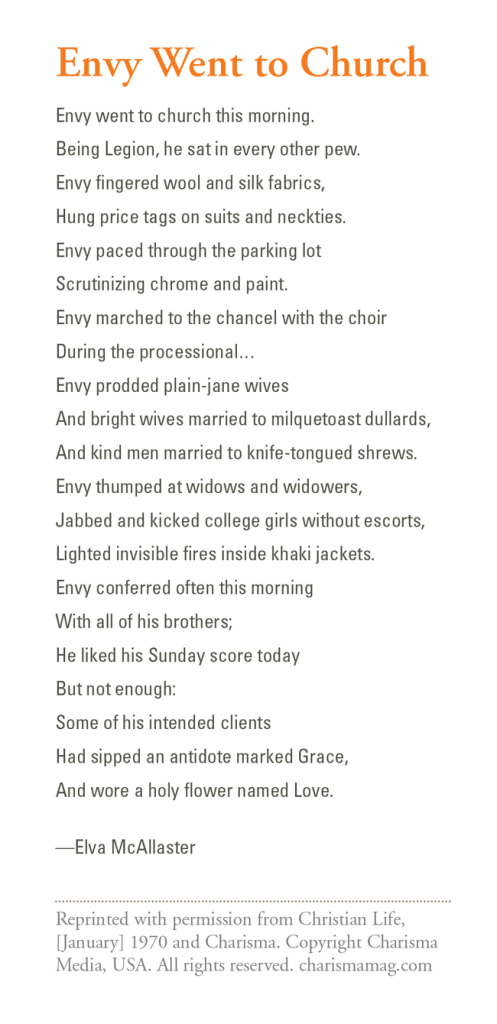

Elva McAllaster, or “Dr. Mac” as she was known on campus, taught at Greenville College for more than three decades. She retired in 1988, but continued to serve the College as poet-in-residence until her death in 1997. She published more than 300 poems and short stories in magazines and newspapers worldwide, and six books including three of poetry, two nonfiction volumes, and one novel.

All a love story

None of her published work falls in the category of love story, yet it is all a love story. Her written words were born of her love for asking questions, imagining possibilities, and articulating ideas with vivid word pictures that help others learn, too. “Learning is a joyous enterprise,” she reminded her students, whom she treated as fellow companions on an adventure. The staff of the 1964 Vista yearbook dedicated the volume to Dr. Mac, calling her “contagiously enthusiastic as a teacher” and “herself, a continual student.”

“I very seldom lecture for many consecutive minutes,” she observed. “For good or for ill, my classrooms are cooperative enterprises; I toss out the questions and coordinate the responses . . . I’m more like the conductor of a symphony than the solo pianist.”

Professor of the human heart

If literature is life transposed to an art form then Dr. Mac was a professor of life. Scores of letters stored in the GC archives give evidence that her students regarded her so. Upon hearing of her retirement, Dr. Edward Knox ’62 penned, “She may have had the title of professor of English, but she was really an inadequately disguised professor of the human heart. I give thanks for her love of literature, her tender heart and her keen interest in the whole student.”

Elva McAllaster treasured a rural Kansas upbringing, the glorious beauty of a western sunset, and warm memories of a family homestead where she was blessed with precious lessons in gratitude, faith, and joy. Yet, she is buried not far from the College in Montrose Cemetery, very near the grave of her mentor and friend, Mary Tenney. The place is fitting for one who so cherished GC that she chose again and again to make it her home.

Today, the honors program at GC bears McAllaster’s name, and each year in her name a new class of students embraces the rigors of academic excellence. If Dr. Mac stood amongst them to launch this adventure, she might start with table linens, crumpets, and a steaming teakettle. Then again, she might let loose a jubilant “war whoop,” the kind she was known to vigorously release at the start of an All College Hike. Learning, after all, is a joyous enterprise.

Comments from Eugene Peterson originally appeared in Seattle Pacific University’s Response, [Autumn] 2011.

This article originally appeared in the Fall 2012 issue of The RECORD, for Alumni and Friends of Greenville University.