I wanted to know the expert technique of applying mascara in front of a locker-room mirror to impress some boy in math class. God had something else in mind…

The last time I saw my mother, she was asleep in her bed. The afternoon sunlight poured through the windows over her. No cares, no schedule, no pressing needs . . . nothing but a welcome nap on this beautiful summer day.

Then again, for the record . . . I was just a kid. Also for the record, who was I fooling?

Pain pills, mineral oil, Q-tips, distilled water and crumpled tissues cluttered the bedside table. A respirator hummed. Her wig perched on a stand on the dresser seemed a relic of long ago when we all feigned normalcy. (Long ago was 12 months.) The wig didn’t matter anymore.

This day had its own struggles, just like the day before. But not like the day that would follow, I soon discovered.

No trace

Sometime during the night, all trace of sickness disappeared: the pills, the machine, the bedclothes, my mother.

When I rounded the corner from my room the next morning and peeked in hers, sunlight poured through the windows onto an empty bed, neatly made up with the bedspread smoothed from head to foot, and everything tucked into place.

The room was oddly tidy and clutter-free. The bedside table contained only a lamp, clock and phone.

In the kitchen, a strange male voice attempted a telephone conversation.

“Mary passed,” it said. Long pause. “Last night.” Long pause. Crying.

It was my dad.

After a moment I heard my aunt’s more normal voice identify herself to the listener and supply details he could not. My breath grew short. I took the strangeness in. I listened from a distance and resolved not to go out to them for that would force immediate acceptance of reality.

Instead, I lingered by my mother’s bed and made a last ditch attempt to wish for the impossible: to have her here again, no matter how sick, no matter how fragile, no matter how cancer-wasted.

No matter how pale. No matter the coma. No matter the bald spots. No matter if the radiation had no effect. No matter if she couldn’t swallow those pills anymore. No matter if she didn’t know that it was she who soiled the bedclothes.

No matter if she couldn’t respond to my whispers. No matter if she could only think the words she had spoken slowly and dryly weeks earlier, “I’m trying.”

I wanted my mother back in the sunlight, no matter anything else, back where my cheek could softly brush against hers, back where I could plant a very gentle kiss on her face. Back where I could whisper that I loved her and know that even in her pained silence, she was thinking her response that she loved me.

I had just turned 14.

My real mother

Early on in my mother’s illness she traveled to Mayo Clinic every two weeks to receive cobalt treatments, an aggressive, experimental effort to zap the cancerous tumors with radiation. The American Cancer Society helped finance the treatment.

She made the first trip with my father, driving from Chicago to Rochester, Minnesota. Later trips, however, she made alone by air because my father had to work, and calling on relatives to stay with us four children burdened others.

She boarded in the home of two retired schoolteachers who rented out rooms to Mayo patients. She stayed in a basement room and commuted by cab to the clinic. She sent post cards to us, and letters that described Rochester, its medical campuses and underground walkways. She sounded like a different person all alone up there.

She wrote about buying a paperback to read to pass the hours she spent waiting, waiting for appointments, waiting for transportation, waiting for treatment.

She missed us.

She saw a movie— Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner—in a theater one afternoon. When did I ever know her to go to a movie?

She always liked Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn. I didn’t know who they were.

She missed us terribly.

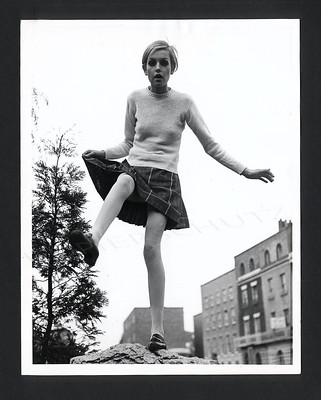

My sister and I accompanied her on a subsequent trip. In those days it was appropriate to dress up for plane travel. I wore a navy hounds tooth checked wool suit, a like-new hand-me-down from my ever-stylish older cousin, a fashionista with well-stocked closets and a mother who enjoyed recreational shopping.

I liked the ensemble, and it fit me fine. The skirt, however, was longer than the miniskirts that were all the rage.

Oh well . . . I simply rolled the waistband and rolled it again to achieve a length I deemed acceptably trendy. My mother disagreed with the makeshift alteration, and we “had words.”

The mother I wanted

The disagreement only reminded me that deep down I wanted a mother who would understand popular styles, and agree to my sporting the short skirts that everyone else was wearing. How could she possibly dismiss the fact that I stood out from all the other girls in my school. Couldn’t she see that I was a dowdy slave to her unreasonable standards for modesty?

(As a young teen, I was particularly gifted in drama.)

And, while we are on the topic, I also wanted a mother who would let me spend my money on records. My friend Cindy had a whole case full of 45-singles—the Beatles, the Dave Clark Five, the Young Rascals, the Zombies. I had one 45 acquired from a sixth grade Christmas party “grab bag.” I definitely wanted more.

I also wanted a mother who would let me go to the movies with Cindy, even though her older “foul-mouthed” brothers would be there too.

I wanted a mother who could see beyond my short, curly red hair and share my vision for a long, straight shiny look like Jean Shrimpton’s.

I wanted a mother who knew who Jean Shrimpton was.

I wanted a mother who would teach me the secrets of talking to boys and tell me how to screw up the courage to ask Steve to skate with me at Bobbie’s roller rink party, having heard from Cindy that he told Dan he would . . . if I asked.

I wanted a mother who would reassure me that 13-year-old boys deeply admired extreme shyness in 13-year-old girls, and that eyeglasses were sort of secret code for “fun to be with” and “flirty,” that they deemed a girl who quietly inhabited a corner in the schoolyard with a book during recess as intriguing, mysteriously different from the usual crowd of gossipy girls and worth pursuit.

I wanted a mother who would understand my need for lip gloss among other things.

I wanted a mother who would surprise me with a subscription to Seventeen Magazine, and let me wear fishnet stockings, one who would cure my blues by suggesting that we go out before dinner to get my ears pierced.

I wanted a mother who would agree that the bedroom I shared with my two younger sisters was intolerably small, one who would tell my father that we must finish the basement for my sake . . . my life depended on a room of my own. This was an urgent matter.

I wanted a mother who would slap my sister for making a joke about my developing breasts.

But, what was I thinking? This was not a mother. This was a perpetual green light, a well-inked stamp of approval, a fantasy friend masquerading as mother.

I didn’t really want this Barbie doll mom. I just wanted someone who would empathize with the changes I was enduring—someone who could assure me that I would survive this hormonal chaos and this leap into womanhood.

But, realistically how could my mother assure me of survival, when survival wasn’t exactly her area of expertise? I was overwhelmed.

Those pesky bilingual years

I was having trouble with the bi-lingual aspect of my life. This “teenage” language I needed to learn was about as confusing to me as the unspoken “death and dying” conversations we tip-toed around at home.

I watched girls spend great chunks of time devoted to their hair, budding make-up skills and style.

They lined up at the mirrors in the locker room after gym class, primping and adjusting and detailing their appearances. I wanted to know their secrets, but honestly I was having trouble just staying awake at school.

Meet you at midnight (again)

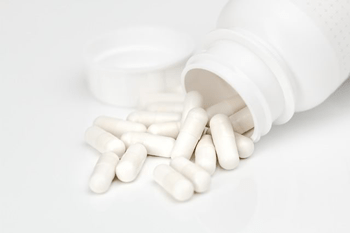

By the time I was 13, the system we had in place at home for administering the midnight pain pills to my mother involved two people—my father and either my sister or me. My father would awaken the “daughter on call” who would drowsily follow him into our parents’ room to help him sit my mother up in bed so that she could swallow the pills.

My mother was weak, and we needed to take care not to hurt her. Somehow he and she managed to scoot her to a crosswise position on the bed, with her legs hanging off the bed. Then, with both of us facing her, one on her left and one on her right, we each cupped an elbow in our hands, and waited for her to grab our arms as we eased her up to a sitting position.

How and where we touched her was critical to her comfort. Then my father would swab her tongue with mineral oil to make it easier for her to swallow because the radiation treatments dried up her tears and saliva. With a ready glass of water—distilled was best—she’d take the pills.

The system evolved from my dad’s creative problem solving, my mother’s willingness to follow his lead, and trial and error. The two tiny pills took forever to go down. I fell asleep on my feet often, waiting, just waiting for the moment when we could reverse the “lifting up” process and perform the “let down.”

During one of these nights, she was aware that my dad and I were waiting on her to swallow a pill. After several failed attempts, she looked up at us and whispered dryly, “I’m trying.”

Trying

I knew she was trying. It took focus and determination for her to accomplish that pill swallow. This was a skill she had figured out and practiced many times over. But as she grew less able, what used to work became ineffective. She would have to rethink the process, and tweak it to make it work anew.

This is how my parents faced the challenge of cancer. They broke problems down and figured out solutions—little tests of ingenuity and execution. It was their nature to make a way and not give up.

- When my mother could not sit up on her own, my father helped her up.

- When even his gentle bear-hug lift proved too painful, he enlisted in the help of a daughter.

- When the nightly interruption took its toll on one girl, he adjusted the plan to include the other daughter, alternating each night.

- When mere water gave insufficient lubrication to down the pill, a coating of mineral oil on the tongue seemed to help.

Relentless problem solving

- When tap water wouldn’t satisfy, distilled water did the trick.

- When cotton sheets restricted her movement and caused pain, a set of nylon sheets reclaimed some comfort.

- When her pain at night became too great, and every movement troubled her, my dad—incredibly self-disciplined—adjusted his position more toward his side of the bed to reduce any disturbance to my mother.

- When my mother required daytime help, a schedule of relatives supplemented the hire of a part-time nurse and the regular after-school assistance of my sister and me.

- When meal preparation became an issue, simple mixes and boxed dinners like macaroni and cheese and Hamburger Helper appeared in our cupboards, and detailed notes in my dad’s handwriting appeared on the kitchen counter, directing us in what to make.

Dad’s ingenuity kept hope alive

It seemed as though my father’s ideas would never fail us or run dry. There was always something new to try . . . a new solution to implement, a new hope. He thought each problem through; he gave up on nothing.

They were remarkable partners—my dad and mom.

My father’s unfailing tenderness toward my mom spoke of his great and deep love for her. My mother—willing to find even the tiniest scrap of strength and “try”—responded as best she could.

And somewhere in there, just when I thought I needed to know the expert technique of applying mascara in front of a locker-room mirror, God led me to a front row seat where I saw profound selflessness and enduring love unfold day by day.

By summer’s end, I knew that the make-up and miniskirts, much like the wig on its dresser stand, didn’t matter.