By U.S. Army veteran Charles Morris. Edited by Carla Morris.

All eyes are on Afghanistan again.

Suicide bombers just blew up more than a dozen American military personnel at the Kabul airport. U.S. President Joe Biden responded with a statement, “We will not forgive. We will not forget.”

U.S. drones then killed two low-level, unnamed ISIS-K operatives in Afghanistan.

As of this morning, no U.S. military personnel remain in Afghanistan, but hundreds of American civilians and tens of thousands of Afghans who collaborated with America are sill there. Opponents of President Biden say he abandoned them. The Pentagon, however, says they were warned more than a week ago. In other words, they chose to stay.

“We will not forgive. We will not forget.”

Forgiveness is a frame of moral evaluation that renders no punishment for wrongs. It requires severe control of emotions, actions, and words.

Forgiveness engages no retribution, no incrimination, and no revenge. It engages no retaliation in acts or words, and no retaliation in even deeper human realities. Forgiveness is a severe moral value.

Amnesty, on the other hand, is a limited, legal frame. It comes from the same root as “amnesia.” Think of it as legal forgetfulness that removes punishment from the picture. Wrongs are committed, but those in charge say, “Forget it.”

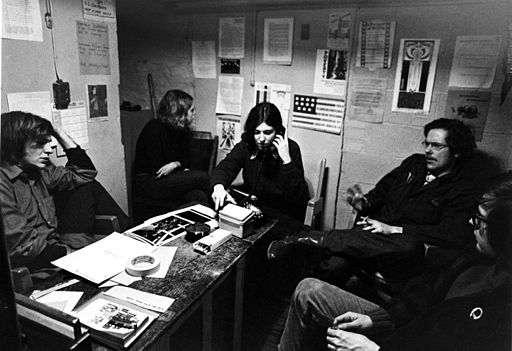

In 1971, many U.S. citizens called for amnesty toward war resisters who had dodged the draft. Then President Nixon said in a speech, “Amnesty is forgiveness. We cannot forgive.”

“As we forgive others.”

When President Biden said “We will not forgive,” I thought of Nixon and the letter I sent to Nixon in response to his speech. I asked the president how many times he had spoken the prayer, “Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us.”

“You will not be forgiven,” I wrote. At the time, I could not imagine the unforgiveness Richard Nixon would suffer, but I knew it would happen. Words matter.

Years later, after the Islamic terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, I wrote a letter to another sitting United States president. I cautioned President George W. Bush: “Do not respond militarily.”

But the U.S. did respond militarily. The response I deemed wrong bred other conflicts, today’s conflict in Afghanistan among them.

Pardon

Folks largely remember President Gerald Ford for pardoning Richard Nixon. Before that, however, Ford started a process of U.S. Government amnesty toward draft dodgers, those of whom Nixon had said, “We cannot forgive.”

In a speech on August 19, 1974, at a convention of the Veterans of Foreign Wars, Ford talked not of forgiveness, but of healing. Amnesty, he said, would pave the way for healing.

War veterans, those of us most sinned against by draft dodgers, know we need healing and forgiveness.

Cursed at, spit upon

In 1971, when I wrote to President Nixon, I had just returned to “the States” from Viet Nam, where I had served since 1969. I was among the soldiers who were greeted at SeaTac airport by spittle and curses from righteous citizens who hated the war.

I thought I had “skin in the game” with respect to amnesty toward draft dodgers. Still, I believed forgiveness was good. It was unquestionably difficult and severe, but good.

Amnesty did not carry the weight that full forgiveness carried, but it provided a way to begin the needed healing.

Nixon, though wrong, remained unforgiven. Ford, though correct, was forgotten. Bush and Biden did what people expected of them.

I still think it’s good to forgive. Difficult? Unquestionably. Severe? Yes. But good. Socio-political amnesia is not forgiveness, but it can begin needed healing.

Amnesty

I propose a general amnesty toward anyone on “the other side.” I do not expect it, but I propose it. I proposed it to Nixon, and I proposed it to Bush. I now, propose it to all righteous citizens. I need forgiveness for my sins; I suspect others need forgiveness for theirs, too.

Jesus forgave his killers as he died. He did it out loud. He did it in public. He was naked, in plain sight of anyone who would look. Forgiveness is difficult and severe.

Anger, on the other hand, is natural and easy. Retaliation and retribution are expected. Amnesty is just a small step in the right direction, easily overlooked.

I have done wrong, because I am wrong. Spit on me and curse me, if you choose. That is exactly how righteous citizens treated Jesus on his way to the cross. Still, I propose a general amnesty toward anyone on “the other side,” no matter what the divisive issue may be.

You do not have to agree with me. You may think I’m wrong, and that you are right. I’ve experienced that a few times. I’m not good, but I try to begin to forgive.

You do not have to be right for Jesus to love you and forgive you. I speak from experience about that. He forgave me and loved me when I was wrong. Good God! I’m still wrong! Jesus loves me. Jesus forgives me. Jesus tells me to pray, “Forgive us our sins as we forgive those who sin against us.”

Forgiveness is difficult. If the difficulty leans toward downright impossible in your mind, I propose a little step in the right direction: amnesty.

Charles Morris

08/31/2021

Photos from top to bottom: (1) Extended hand image by Jackson David from Pixabay; (2) Flag-draped coffins: U.S. Central Command Public Affairs, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (3) Richard Nixon, The Nixon library, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (4) Vietnam war resisters, Laura Jones, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons; (5)Protesters: uwdigitalcollections, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons